Why we need an independent commission to end gerrymandering once and for all

Jennifer Bremer, Fair Districts NC

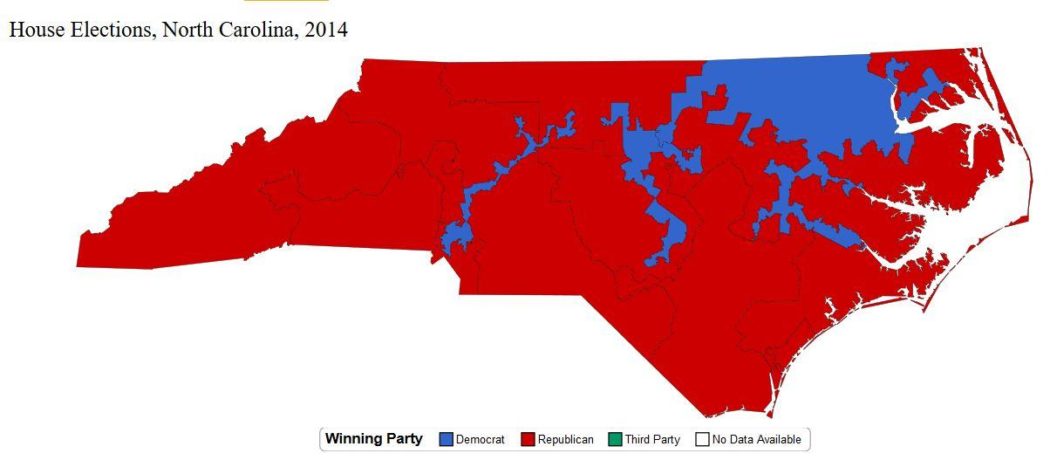

Gerrymandering is North Carolina’s political blood sport. Whether Democrats or Republicans rig the maps, the party in charge can entrench itself in power, drawing maps that win its candidates a larger share of the seats than they earn at the ballot box.

With the next redistricting coming up in 2021, we need a solution that will end extreme gerrymandering once and for all. Tinkering with the legislature’s map-drawing methods will not get the job done. We need an independent redistricting commission.

Reformers point to California’s citizens’ commission as an ideal model, one where the legislature has no role in the process at all: no role in picking the commissioners, no role in drawing district lines, and no role in approving the maps.

Ideal or not, this option is off the table for North Carolina. Californians can pass petitions to put a law or constitutional amendment right on the ballot without the legislature having a say at all. We can’t. Whether it’s a law or a constitutional amendment, it has to go through the legislature.

California is the only state where politicians have no role in redistricting. No legislature in the country with the power to draw the maps has ever voted to give that power away entirely. Why would they?

Legislatures have created commissions in 11 states, though. And every one of them preserves a role for politicians, either in naming at least some of the commissioners or in approving the maps. If we want to end extreme gerrymandering, that’s our choice: preserve a role for the legislature in the front of the commission process—naming some of the commissioners—or in the back of the process—approving the maps.

Which is better? Some reform models on the table in North Carolina would keep the legislature in charge of the back end, but this is truly risky. Those models typically allow the legislature to vote down three maps presented to them and then draw any map they want. It’s pretty easy to imagine how it would go here.

Reforms put forward in other states are much more likely to give the legislature a role in the front of the process, usually naming some of the commissioners (but rarely all). They often limit who can be named to keep political operatives—and their relatives—off the commission.

The bills also provide for inclusion of unaffiliated voters on the commission as well as members of the two major parties. Unaffiliateds are the fastest growing voter group in North Carolina, especially among young voters. They deserve a seat at the table.

Finally, well-crafted reforms create a transparent process with multiple routes for citizen involvement, from hearings and public comment on draft maps, to maps proposed by citizens themselves. Many limit what data can be used, recognizing that it impossible to gerrymander without political data, and prohibit protection of incumbents. They specify what criteria must be used, including compliance with constitutional and racial equity requirements.

To be sure, it would be easier to go for an even more limited reform that left the legislature in charge of drawing the maps, but set tight criteria and ruled out use of political data. Some reform advocates believe this simpler approach can prevent the legislature from drawing rigged maps.

Like most simple solutions, this one sounds good but doesn’t get the job done. Florida tried it in 2010, adopting a constitutional amendment with strong criteria and rules against partisan maps. The legislature drew an extreme gerrymander anyway. Five years of court battles, judicial orders, and legislative deadlock followed. Finally, the court had to draw the maps. Florida is now looking at commission models.

We can’t let another decade of rigged maps destroy our democracy. We need reform, but we don’t need perfection. We need what the League of Women Voters has called “Reasonable Redistricting Reform”—a commission that keeps the legislature involved in choosing commissioners, provides for an open process protected from partisan interference, and makes the maps final on the commission’s vote alone.

That’s a recipe for a reform that can get the job done and pass the legislature in time for 2021.

Jennifer Bremer leads Fair Districts NC, a nonpartisan coalition working for redistricting reform in North Carolina.

There are no comments

Add yours