C-sections, where an infant is surgically removed from the uterus through an abdominal incision, are important, often life-saving procedures. While a vaginal birth is the safest and least complicated method of delivery, the birthing team may opt for a C-sections for the following reasons: [1]

- Your cervix is not dilating

- Pushing is taking too long

- The baby is distressed

- The baby is breech (bottom first) or transverse (side/shoulders first)

- You are having twins, triplets, or more

- The umbilical cord is coming out before the baby

- There is something blocking the birth canal (ex. a uterine fibroid or pelvic fracture)

- You have had a previous C-section

- There is another health reason (ex. a heart or brain condition that makes pushing dangerous)

Laboring and birth is a psychologically and physiologically stressful event for both mother and baby. In general, it is better for labor and delivery to be as fast as possible to minimize this stressful time and potential complications.

Accordingly, about 34% of C-sections are due to “labor arrest,” or labor taking too long. About 23% are due to “non-reassuring fetal tracing,” or fetal distress, and about 17% are due to “malpresentation,” which is any fetal presentation other than head first. The remaining 26% of C-sections are due to less common indications such as multiple gestation, preeclampsia, and maternal request. [2]

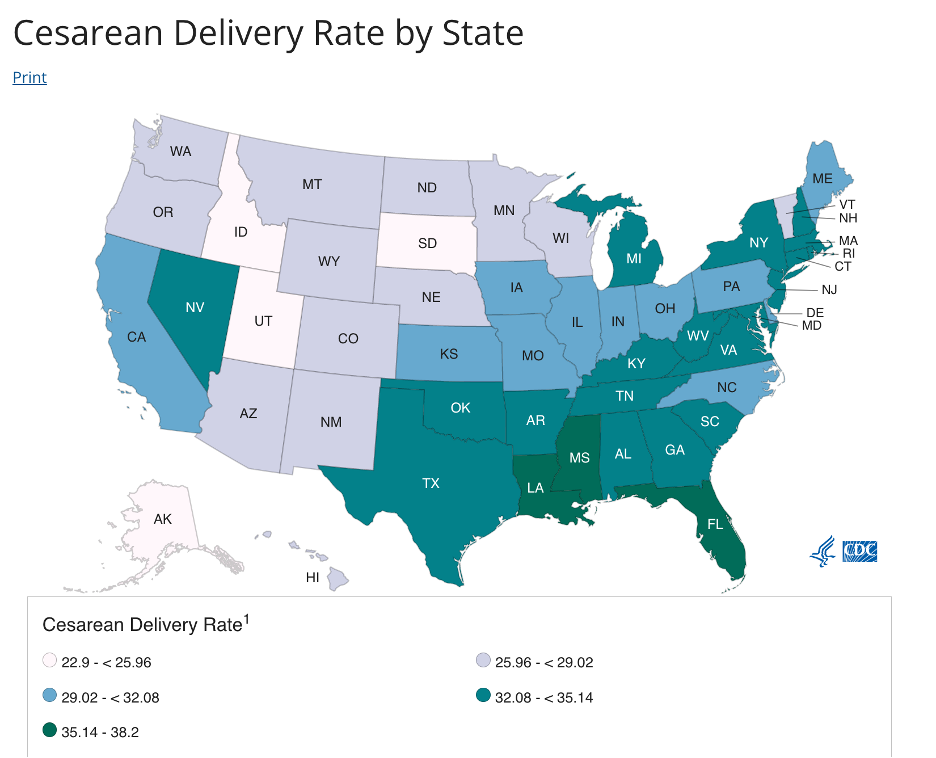

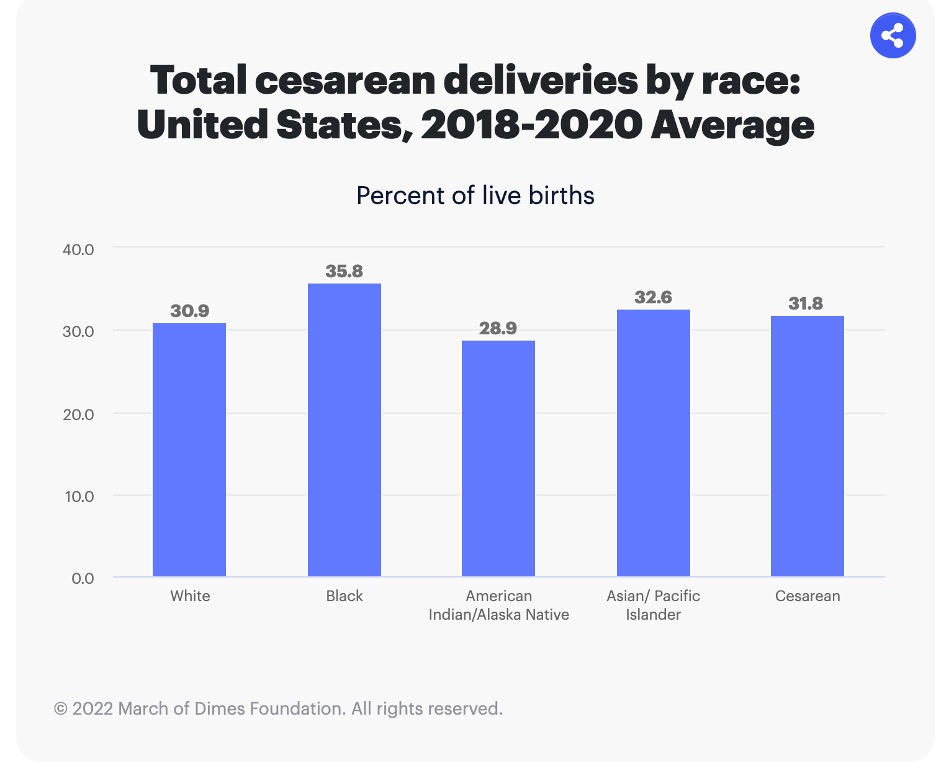

Interestingly, the U.S. has one of the highest rates of cesarean deliveries compared to other developed countries. In 2020, about 31.8% of babies were delivered via C-section, totaling 1,18,692, compared to 2,462,904 vaginal births. Additionally, the rate of C-sections has generally increased every year since 1996, when it accounted for only 20.7% of births. From 1996 to today, delivery by C-section has increased by 54%.

The rate of C-sections also follows racial and ethnic trends seen in other parts of obstetrical science. Although C-sections have increased for all groups, non-Hispanic Black women continue to have the highest rate of C-sections (36.3%), followed by Hispanic women (31.4%), then non-Hispanic white women (30.8%).

Cesarean deliveries, while life-saving under certain conditions, are generally riskier than typical vaginal births. C-sections carry serious risks, including cardiac arrest, infections, blood clots, and other surgical complications. [3] They require more time in the hospital to recover and are often more painful than vaginal births.

Interestingly, the low-risk C-section rate continues to increase. We often think of C-sections as needed in emergency situations where vaginal births cannot take place, which is absolutely true. However, the low-risk C-section rate looks at these deliveries performed without any initially obvious reason for needing surgery. A low-risk C-section is defined as cesarean delivery among “nulliparous (first birth), term (37 weeks gestation completed based on obstetric estimate), singleton (one fetus), and cephalic (head first).” [4]

In other words, mothers and OB/GYNs are opting for C-sections in labor situations that would usually be considered low-risk, and thus less likely of needing a C-section in the first place.

To be clear, just because the delivery was considered a “low-risk cesarean delivery” does not mean that the C-section was not clinically indicated at the time. It just means that, overall, this type of pregnancy and delivery are statistically less likely to need a C-section.

C-sections for “non-medical reasons,” such as the mother’s request, are also on the rise. Common reasons why women choose scheduled C-sections include:

- Belief that it is safer for the baby

- Belief that it is safer for their own body

- Concern about pelvic floor/vaginal trauma after vaginal birth

- Scheduling convenience, either for themselves or infant’s caregivers

- Avoidance of labor/delivery pain [5]

It has been found, however, that women who request a C-section for “no apparent medical reason,” often report trauma such as sexual abuse or a previous traumatic birth. Because of this, these women feel that delivery via C-section is a better option for them psychologically, emotionally, and/or physically. [6]

Overall, the reasons women choose planned C-sections when vaginal delivery is possible are incredibly personal. Women should be equipped with all relevant information about the risks and benefits of C-sections vs. vaginal births, as well as access to resources, such as individualized therapy or educational birthing classes, to aid in their decision. If this is accomplished, we should trust women to make the right decision for their own bodies.

On the other hand, C-sections for “vague medical indications,” such as labor taking too long and presumed fetal distress, continue to rise in developed countries, like the U.S. Researchers cite a rapid rise in C-sections from 1996 to 2011 “without clear evidence of concomitant decreases in maternal or neonatal morbidity or mortality.” This has led to a concern that C-sections are overused in situations where maternal and fetal well-being are not at risk and vaginal birth could have taken place. [7]

Doctors, scientists, and other health care providers have suggested reform regarding the current requisite conditions for switching from vaginal birth to C-section. For example, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists cites that labor dystocia (labor taking too long) may not be sufficient reason to opt for C-section, because “contemporary labor progresses at a rate substantially lower than what was historically taught.”

In addition, C-sections because of presumed fetal compromise (concern about infant’s well-being) may be decreased by improved, standardized fetal heart monitoring.

Research has also shown that continuous labor and delivery support, whether through the hospital’s nursing staff, midwives, or doulas, has also been shown to reduce C-section rates.

Overall, there are many areas that could be addressed to reduce C-section rates and allow women to have vaginal births more frequently.

Fortunately, two important initiatives are in the works to reduce women’s risk of needing subsequent C-sections, including VBAC (Vaginal Birth After Cesarean) and improved postpartum care.

For centuries, if women delivered via C-section, they had to deliver by C-section for every subsequent child. After the uterus had been cut, healed over, and scarred from surgery, doctors presumed that the organ would be too compromised to deliver vaginally. Among other things, doctors feared that the uterine scar could rupture from the strain of labor, causing the baby to be “born” into the mother’s abdominal cavity. This would require immediate, emergency abdominal surgery and risk both the mother’s and baby’s lives.

Around the 1980s and 90s, however, the National Institute of Health began to revise whether C-sections after a primary cesarean were truly medically necessary. Vaginal births, remember, are generally less dangerous and painful. Multiple C-sections can also endanger future pregnancies, because it raises the risk of placental problems. [8] In addition, many women who give birth cite wanting to experience a vaginal delivery, rather than a C-section. Thus came the VBAC, which empowered eligible women to attempt vaginal delivery, even if they have had a previous C-section.

To increase the likelihood of a successful VBAC, a pregnant person may demonstrate the following things: [9]

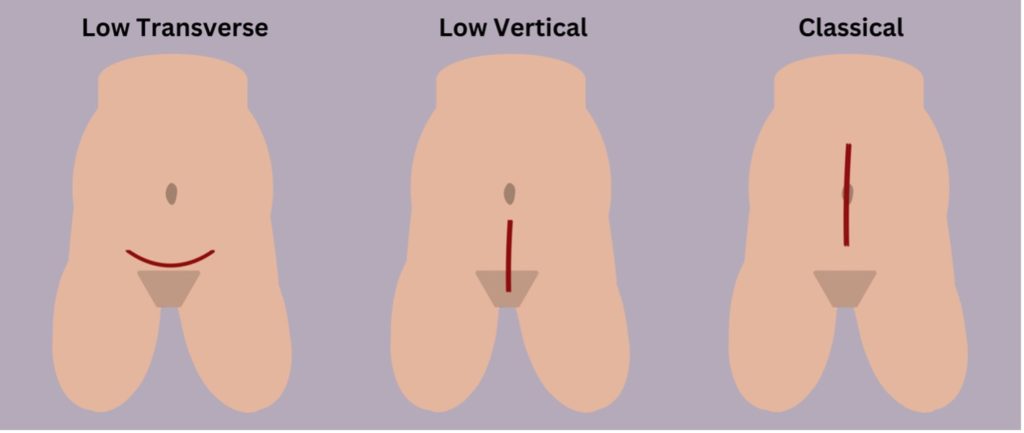

- Must have had a previous C-section using a low transverse or low vertical incision, not a classical incision (this type of incision increases the risk of uterine rupture)

- Never had a previous uterine rupture

- Never had other surgeries on their uterus (such as fibroid removal)

- Has had a successful vaginal birth at least once before

- Has had more than 18 months to recover since last delivery

- Have no health concerns that would make a C-section necessary (such as placental problems)

- Must be delivering in a hospital*

Even with all of these considerations, about 90% of women who have had a previous C-section are candidates for VBAC.

Note: each of these incisions would be made on the body of the uterus, not on the skin of the abdomen.

During a VBAC, a woman progresses through labor in the same fashion as any vaginal delivery. The key difference is that the hospital delivery staff is prepared to do a repeat C-section if needed and pays very close attention to the infant’s heart rate. [10]

In addition to VBAC, reproductive rights advocates are calling for longer, more comprehensive postpartum care coverage to reduce C-section rates. The thinking is that better postpartum care will help the after-birth healing process and may aid in family planning, which can both reduce the risk of future C-sections.

MACPAC, a federal office who advises Congress on Medicaid, recommends extending the coverage to twelve months postpartum, a huge jump from the current two months covered under most plans. Currently, 25% of women who were enrolled in Medicaid at birth report becoming uninsured postpartum. If Medicaid were to extend coverage to 12 months, approximately 123,000 uninsured new mothers would gain health insurance. [11]

Better patient education on the risk/benefit profile for C-sections, as well as improved postpartum care and continued research on VBAC will help reduce cesarean rates.

SOURCES:

[1] Center for Disease Control [2] American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists [3] MACPAC Medicaid Role in Maternal Health [4] CDC [5] Lavender T, Hofmeyr GJ, Neilson JP, Kingdon C, Gyte GM. “Caesarean section for non-medical reasons at term.” Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012 Mar 14;2012(3) [6] “Caesarean section for non-medical reasons at term” [7] ACOG [8] Mayo Clinic [9] Mayo Clinc* These considerations increase the likelihood of a successful VBAC, but they do not disbar VBAC or guarantee a successful VBAC

[10] Mayo Clinic [11] MACPAC “Advancing Maternal and Infant Health by Extending the Postpartum Coverage Period”

This article was originally published on March 15, 2023.

Emma Hergenrother is from Ridgefield, CT. She is excited to be currently living in Durham, NC, and contributed to Women AdvaNCe as a Research Fellow. Earning her Bachelor’s from Princeton University, Emma majored in religion with a focus on the relationship between religious attitudes, theological beliefs, and environmentalism. Since graduation, Emma has worked for an affordable housing nonprofit in Connecticut, and is currently studying to become a physician with a focus on pediatric health. In her free time, Emma enjoys cooking with her partner, going for long walks, and diving into her latest audiobook.

Emma Hergenrother is from Ridgefield, CT. She is excited to be currently living in Durham, NC, and contributed to Women AdvaNCe as a Research Fellow. Earning her Bachelor’s from Princeton University, Emma majored in religion with a focus on the relationship between religious attitudes, theological beliefs, and environmentalism. Since graduation, Emma has worked for an affordable housing nonprofit in Connecticut, and is currently studying to become a physician with a focus on pediatric health. In her free time, Emma enjoys cooking with her partner, going for long walks, and diving into her latest audiobook.

There are no comments

Add yours