If you have ever been pregnant, you know how vitally important prenatal visits are to your own health, as well as the health and wellness of your future baby.

If you have ever been pregnant, you know how vitally important prenatal visits are to your own health, as well as the health and wellness of your future baby.

During these visits, nursing staff will routinely record your height, weight, and blood pressure to monitor your growth and physiological stress. An ultrasound tech will glide a probe over your gel-covered belly and tell you about your fetus’s growth and positioning. Your OB/GYN will perform regular pelvic and cervical exams to ensure that your body is accommodating your expanding uterus. They will take a blood sample to confirm your blood type as well as screen for diseases that could be passed to your fetus, such as HIV, Hep B, and syphilis. Your provider will pore over your personal and family medical history to determine a risk for congenital diseases. They may recommend genetic testing of the amniotic fluid surrounding the fetus to screen for chromosomal anomalies or meeting with a genetic counselor. Doctors, nurses, and techs will discuss your lifestyle habits – nutritious eating, regular exercise, stress management, substance use – to ensure that your body is supporting a healthy pregnancy.

Each of these steps serves a specific, clinical function. However, pregnancy represents a precarious time where your decisions directly affect the development, growth, and well-being health of another. Conception, pregnancy, and birth challenge our cultural values of freedom, autonomy, and individualism. As a pregnant person, you are responsible for the health of a future human being through your own bodily choices.

Throughout a typical, 40-week pregnancy, a pregnant person will attend about 10-15 prenatal visits. These visits begin at a slow frequency, about once per month for the first 28 weeks of gestation, progressing to twice per month until 36 weeks of gestation, and finally once per week until birth.

However, this prenatal schedule represents a stark transition from the medical maintenance schedule to which most reproductive-aged people are accustomed. Most people attend just a few doctor’s appointments per year, if any at all. Becoming pregnant and assuming the corresponding medical responsibility is a time-consuming and stressful commitment. Your life and body transform into the vessel serving another, more vulnerable being. This stress grows exponentially in complex or high-risk pregnancies, where pregnant people may be asked to attend weekly prenatal visits, spend weeks on bed rest, and submit to a particular birth plan (such as a scheduled C-section).[1]

While pregnancy and birth have the potential to be one of the most empowering and profoundly natural experiences a person can have, it has become increasingly medicalized, often at the expense of the pregnant person’s freedom.

However, our health care system places too much value on healthy pregnancies and births alone, while losing sight of pregnancy-capable people’s health preconception and postpartum. Perhaps nothing illuminates this better than the relationship between pregnancy, insurance coverage, and Medicaid.

Medicaid is a government health insurance that is funded by state and federal taxes to provide quality health insurance to financially-vulnerable individuals and households. To be eligible for Medicaid in North Carolina, you must earn a low income AND one of the following:

- Pregnant

- Responsible for a child 18 years of age or younger

- Blind

- Have a disability or a family member in your household with a disability

- Be 65 years of age or older [2]

In other words, Medicaid only exists for people who earn very low incomes and experience another condition that necessitates consistent medical care, such as visual impairment, caring for children, or advanced age.

However, this current system leaves large swatches of people uninsured. For example, some people earn too much money to qualify for Medicaid, which sets income limits at $18,075 for a 1-person household and a $36,908 for 4-person household in North Carolina. However, they still may be unable to afford private health insurance on their current income. In addition, some people who qualify for Medicaid from an income standpoint may not fulfill one of the additional requirements outlined above, and thus do not qualify for Medicaid while also being unable to afford different health insurance.

Despite these barriers, Medicaid is the largest payer for maternity care in the U.S., outspending every private insurance provider. In fact, Medicaid pays for nearly 50% of births in the U.S. [3] This is because being pregnant is a qualifying condition for Medicaid, so, for at least the nine months of pregnancy, previously uninsured pregnant people may be able to qualify for health care through Medicaid.

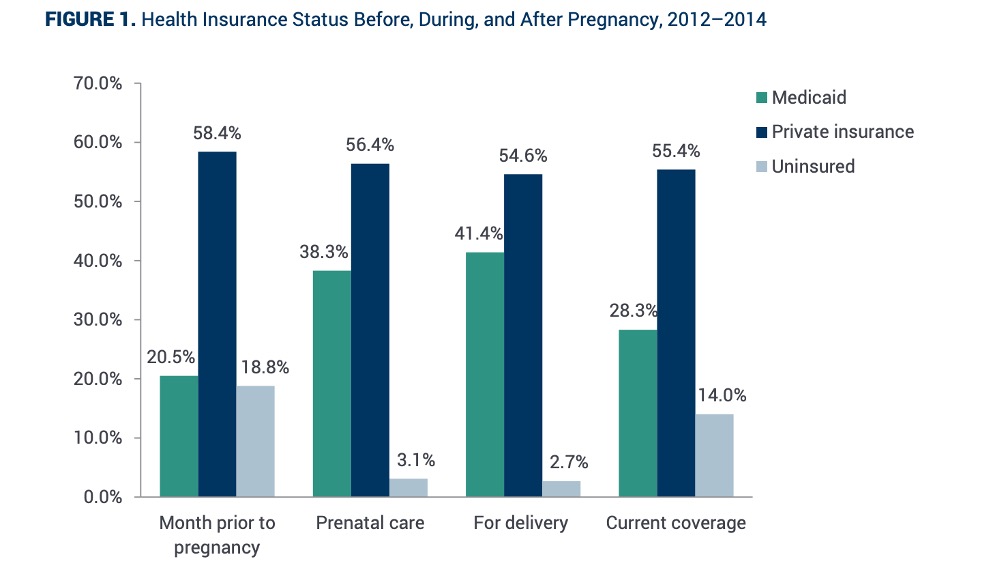

Importantly, Medicaid coverage for pregnancy only begins once a person is confirmed to be pregnant with a formal test. In other words, Medicaid will not cover any preconception health or fertility counseling. In fact, although only 3% of women are medically uninsured at delivery, about 20% of women are uninsured in the month leading up to conception.

In addition, Medicaid will only cover 60 days of health services postpartum, unless the person becomes responsible for their new baby. This leaves behind people who gave birth to a baby for whom they are not responsible (perhaps because of custody issues, deciding to put a baby up for adoption, or being a surrogate) with only 60 days of postpartum care. Although only 3% of women are uninsured at birth, this number jumps to 14% postpartum. [4]

Graph of MACPAC Advising Congress on Medicaid and CHIP Policy

The tie between Medicaid eligibility and pregnancy means that many pregnant people on Medicaid may experience interrupted or delayed care prior to becoming pregnant.[5] While Medicaid assumes responsibility for a large proportion of pregnancy- and birth-related medical care, it leaves pregnancy-capable people uninsured as they consider or prepare for pregnancy prior to conception. This discrepancy in medical insurance – coverage only during pregnancy, not before – may help explain some of the disparities in birth outcomes for infants born to parents on Medicaid.

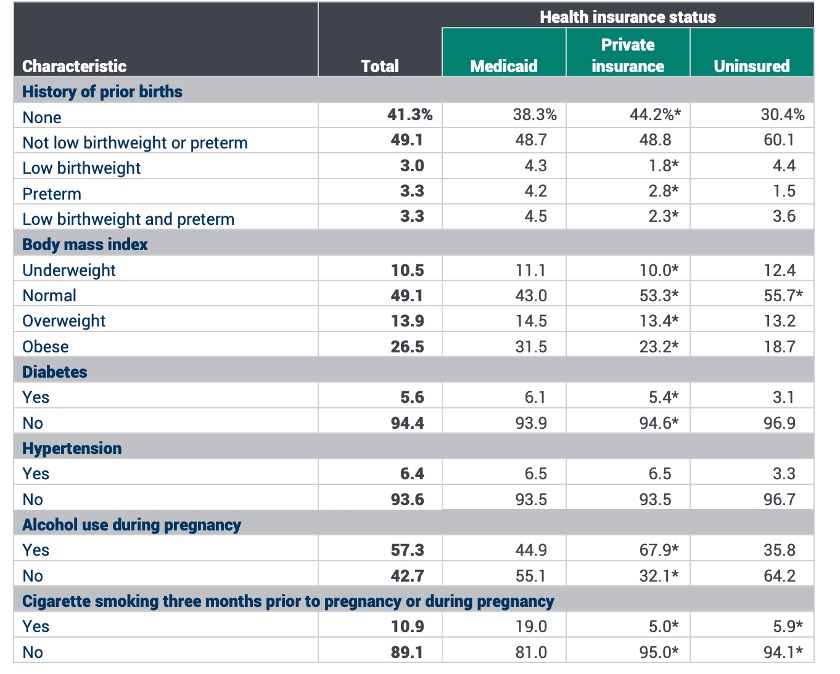

We know that pregnancy-capable people who earn low incomes tend to experience more chronic conditions than middle- and high-income earners. Many of these conditions, such as obesity, diabetes, hypertension, substance use, untreated mental illness, and heart disease, can negatively affect maternal health and birth outcomes. Correspondingly, pregnant people on Medicaid are more likely than privately-insured people to have preterm births, delivery via C-section, and low-birthweight infants. Consequently, infants who are born preterm or with low birthweights are more likely to experience physical and developmental disabilities in their lifetime. [6]

Table of MACPAC’s Analysis of the 2012–2014 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Data, 2017

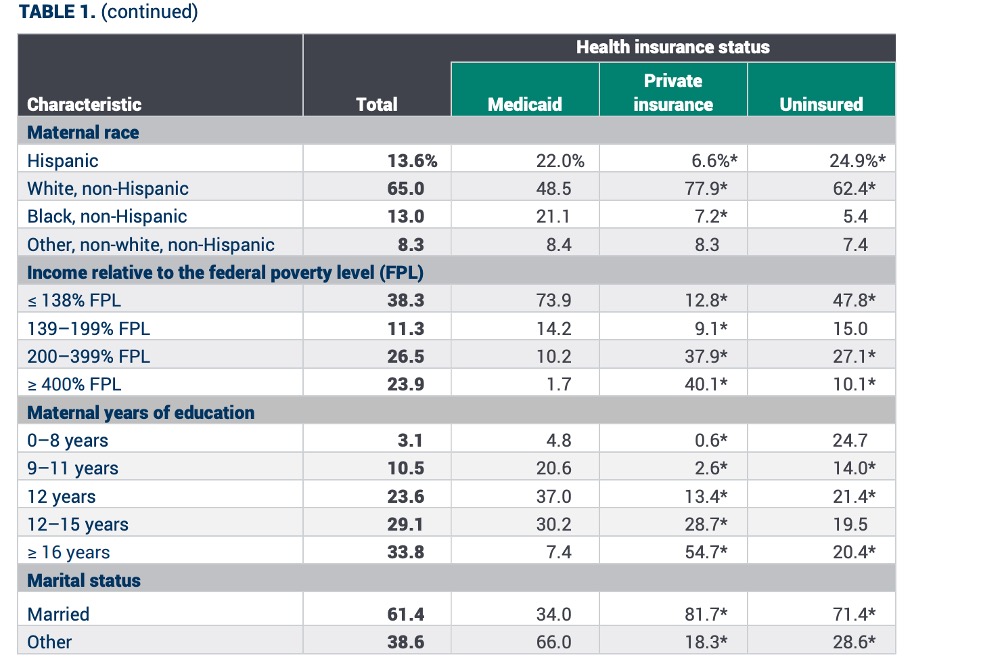

In addition, people who deliver while covered by Medicaid also tend to be younger and less likely to be married, more likely to be Black and/or Hispanic, and have fewer years of total education. Overall, trends in Medicaid coverage at the time of delivery reproduce well-documented disparities in U.S. health care.

Table of MACPAC’s Analysis of the 2012–2014 Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS) Data, 2017

According to the Pregnancy Risk Assessment Monitoring System (PRAMS), pregnant people in the U.S. increasingly experience adverse maternal and birth outcomes.

Although not all these outcomes are life-threatening, life-threatening complications continue to rise. Every year in the U.S., about 700 women die from pregnancy- and birth-related complications up to a year after delivery. An estimated 60% of these deaths are preventable with proper monitoring and treatment. [7]

Maternal mortality varies by timing, with about one third of deaths occurring during pregnancy, one third occurring during or a week after delivery, and one third occurring further postpartum. The leading causes of maternal death are cardiovascular conditions, cerebrovascular events, infection, and obstetric hemorrhage. On the day of delivery, hemorrhage and embolism are the leading causes of death. Postpartum, cardiomyopathy is the leading cause of death. [8]

Black mothers are two to three times more likely to die from pregnancy- and birth-related complications, followed by American Indian mothers. In comparison to white mothers, the mortality rate in the late postpartum period tends to be higher for Black women.

Some of the reasons that mothers die during pregnancy, birth, or postpartum arise from emergency situations that cannot be predicted or are unavoidable. By nature, pregnancy and birth are dangerous. However, many of the deaths that claim mothers’ lives are avoidable and arise from untreated or poorly controlled chronic conditions that endanger the pregnancy, infant’s health, and mother’s health.

The unacceptably high maternal mortality rate, constituted mostly by preventable deaths, underscores the need for complete health care and insurance reform surrounding pregnancy and birth. Many of the health care conditions that endanger pregnancy exist prior to pregnancy. In other words, common chronic conditions like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease pave the way for high maternal and infant mortality rates.

If we want to reduce maternal and infant mortality, we need to start caring about pregnancy-capable people’s health prior to pregnancy and not just in the case of pregnancy.

There is a fundamental backwardness in how the U.S. thinks about healthy reproduction and child-rearing. The structure of Medicaid, where low-income pregnant people may only qualify after the onset of pregnancy and only for 60 days afterwards, sets people up for failure. Being medically uninsured makes the management of chronic disease more difficult and increases the likelihood of pregnancies that endanger the lives of mothers and babies. Given that half of pregnancies are unplanned, it is vital that we can achieve and maintain good health before and during our reproductive years, not only for ourselves but for our future children.

To ensure the healthiest pregnancies, deliveries, and postpartum periods possible, and thus the healthiest babies possible, we must tend to the health of potential mothers and fathers before they face parenthood.

Sources:

[1] Geisinger

[2] NC Medicaid

[3] MACPAC Advising Congress on Medicaid and CHIP Policy

[4] MACPAC

[5] MACPAC

[6] MACPAC

[7] MACPAC

[8] MACPAC Medicaid’s Role in Maternal Health

Emma Hergenrother is from Ridgefield, CT. She is excited to be currently living in Durham, NC, and contributed to Women AdvaNCe as a Research Fellow. Earning her Bachelor’s from Princeton University, Emma majored in religion with a focus on the relationship between religious attitudes, theological beliefs, and environmentalism. Since graduation, Emma has worked for an affordable housing nonprofit in Connecticut, and is currently studying to become a physician with a focus on pediatric health. In her free time, Emma enjoys cooking with her partner, going for long walks, and diving into her latest audiobook.

Emma Hergenrother is from Ridgefield, CT. She is excited to be currently living in Durham, NC, and contributed to Women AdvaNCe as a Research Fellow. Earning her Bachelor’s from Princeton University, Emma majored in religion with a focus on the relationship between religious attitudes, theological beliefs, and environmentalism. Since graduation, Emma has worked for an affordable housing nonprofit in Connecticut, and is currently studying to become a physician with a focus on pediatric health. In her free time, Emma enjoys cooking with her partner, going for long walks, and diving into her latest audiobook.

There are no comments

Add yours