Throughout this series on women’s reproductive care, we often identify women as people with biologically-female anatomy, such as a uterus, vagina, and ovaries. However, we acknowledge that people with this anatomy identify as other genders. We recognize that having this anatomy does not necessarily mean a person is a woman, nor is it a prerequisite for being a woman.

Have you ever heard of Henrietta Lacks?

If you are not immersed in the world of molecular and clinical biology, the odds are you probably have not. However, it is likely that without knowing it, you have benefitted from her incredible contribution to modern medicine.

We all have a lot for which to thank Henrietta Lacks.

Henrietta was not a biologist nor a doctor. In fact, she never worked within health care. Henrietta was, as you and I have been, a patient. But not just any patient, Henrietta was a Black, impoverished, female patient in the Jim Crow South. And it is her status as a patient – as a person who puts their trust in medical professionals to care for their health – that launched Henrietta into unsolicited fame within the world of medicine.

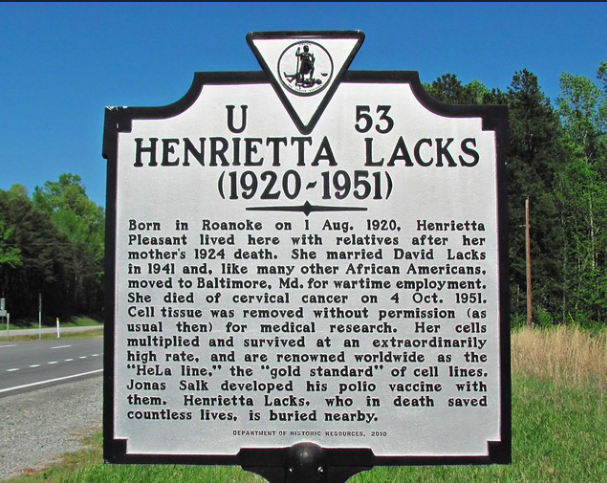

Henrietta was born on August 1, 1920 to a family of tobacco farmers in Roanoke, Virginia. She grew up in a small house with nine siblings, loved to dance, and enjoyed painting the town with her girlfriends (Skloot 43). In 1941, Henrietta married and eventually became a mother to five children.

In 1950, Henrietta began to feel that something was wrong within her body. Sex with her husband had become extremely painful, and she examined herself to find a “knot” at the top of her vagina (Skloot 14). In January 1951, Henrietta brought herself to Johns Hopkins for treatment, the only hospital in the area which accepted Black patients (Skloot 15).

During her initial exam, Henrietta’s doctor, Howard Jones, observed a mass on Henrietta’s cervix, the rubbery tissue at the bottom of the uterus which separates the organ from the vagina. Dr. Jones took a sample of this tissue for biopsy and returned with devastating news – it was malignant cancer (Skloot 17).

As a patient at Johns Hopkins, Henrietta endured rounds of painful radiation, invasive physical exams, and endless medical chatter. Hoping to eliminate, or at least slow, the aggressive cervical cancer, she entrusted her life and well-being to these doctors – none of whom looked like her or shared her life experiences. At some time during her treatment, two additional samples of Henrietta’s cervix were taken, without her knowledge, and given to Dr. George Gey, a cancer researcher at Johns Hopkins (Skloot 33). While studying Henrietta’s cells, Gey’s team made an incredible discovery that changed medical research forever. Henrietta’s cancerous cells could survive in culture (outside of the body) and reproduce new cells at an rate never seen before (Skloot 41). Previously, medical research had been limited because cells in culture could only survive for a matter of days. Armed with Henrietta’s cells, now christened “HeLa” cells, medical experiments on cells in culture became longer, more elaborate, and more ambitious. Medical research that just months before could only have been dreamed of was now a reality.

Today, HeLa cells are present in most molecular biology labs around the world. In fact, there have been so many of these cells produced, that one scientist estimated all the HeLa cells ever grown would weigh a collective 50 million metric tons, or over 110 billion pounds – far outweighing the body mass of the five-foot, 100-something pound woman who once walked the earth (Skloot 2).

While medical experimentation using HeLa cells soared to new heights, Henrietta Lacks herself lived the rest of her days in pain and suffering. Before the end of 1951, just 10 months after her initial appointment with Dr. Jones, Henrietta died of cancer – the same cancer which became one of the greatest contributions to medical research ever recorded. Even today, most of Henrietta’s kin continue to live in poverty, many with severe health issues of their own and without the health insurance to pay for care (Skloot 280). Despite Henrietta’s incredible gift to medicine, the Lacks’ family has reportedly never seen a dime of the billions in revenue dollars which HeLa cells have produced.

Henrietta Lacks’ story embodies two wildly different branches diverging from the same event in her reproductive care. On one side, the research conducted on her cervical cells drove some of contemporary medicine’s greatest breakthroughs and achievements, including the polio vaccine, gene mapping, cancer treatments, and research on HIV/AIDS (Skloot 2). Nonetheless, stories like Henrietta’s have fueled generations of skepticism against medicine and medical research – especially within the Black community – and for good reason: Henrietta never consented to submitting her body to medical research. So even though Henrietta’s contribution has bettered human health as a whole, in a cruel twist, Henrietta and her family have never known this benefit for themselves.

I first learned about Henrietta through Rebecca Skloot’s powerful investigative biography The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. For years, I had seen the book’s bright orange binding in my mother’s living room. Recently, a wave of curiosity inspired me to take the book off the shelf and hold it in my hands. On the cover, I looked into the eyes of Henrietta Lacks – a bright, composed woman carrying herself with confidence and ease. Henrietta is the inspiration for this series – her story exemplifies the immense achievement and immense harm that can be dually effected by women’s reproductive care.

Effective and ethical reproductive care for women is a powerful tool underlying so many important facets of life, including general health, sexual well-being, and the decision to reproduce. Proper care can empower women to lead healthy lives, engage in fulfilling sex lives, fuel research to benefit future generations, and lay the groundwork to raise thriving children.

For the next six weeks, we will explore varying topics in women’s reproductive care, including infant mortality, contraception, sexually transmitted diseases and infections, menstruation, endometriosis, hysterectomies, and menopause. We hope this series will empower women not only to learn about their own bodies, but also to speak honestly and openly with their health care providers about how they can best be served as patients. We will dive into the science behind each of these pressing issues and explore how women can best advocate for themselves and their reproductive health, both in and out of the exam room.

Let’s get started!

Upcoming Article: Friday, November 5th – Infant Mortality in North Carolina

There are no comments

Add yours