It has been a long, hot, brutal summer. It should be our hope that as summer comes to an end, violence in the name of justice will have seen its last days.

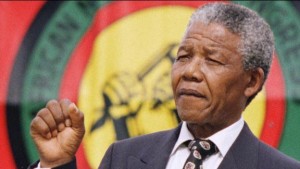

I had dinner with a group of women a few weeks ago. We gathered in honor of the legacy of the late Nelson Rolihlahla Mandela. It was in that moment this group of women – mostly older – talked about the all-too-similar tragedies in our nation. Each longed for the type of leadership Mandela (although not perfectly) modeled.

I first learned about Mandela and apartheid as a young girl visiting the campus of Shaw University. It was there my cousin encouraged me to boycott companies that refused to honor U.S. trade sanctions against South Africa. We wrote letters to government officials we never had the courage to mail, and I wore my “Free Mandela” T-shirt every week as a middle schooler. In fact, I continued wearing it long after Mandela had been freed (before Internet, news traveled slowly in the small towns). It was my first real lesson in civil disobedience.

As far as I was concerned, Mandela’s struggle was symbolic of every injustice a segregated society could hurl at people because of their “otherness.” It wasn’t simply about some problem across the ocean. I grew up hearing stories about segregation in my own country and listening to hip-hop – both of which told me we had not yet overcome.

Learning about Mandela’s struggle against apartheid challenged my young mind to ask, Why does racism against people of color continue showing up all over the globe? That question took summers of reading books and a major in African-American studies to come close to an answer. While the exact answer still eludes me, I often refer people to author and activist, bell hooks.

But Mandela’s victory is an example of what went right…

He watched after years of peaceful protests, police open fire, killing 69 anti-apartheid protesters in the Sharpeville Massacre in 1960. Mandela, along with a group of protesters, responded with more aggressive tactics and was imprisoned for 27 years. Even in his Robben Island cell, he could not escape racism as prison guards continued to give preferential treatment to white and lighter-skinned prisoners. Years later, Mandela arose as an advocate for forgiveness and invited those same guards to be seated in the front row of his presidential inauguration.

Today, people use this idea of forgiveness to suggest silence, but that was never Mandela’s strategy.

I learned more from South African friends as I travel to Johannesburg with a college group and participate in discussions at the University of Witwatersrand where Mandela began his law studies. The economic system struggled from the day-to-day impact under apartheid to a devastation that history books failed to mention.

We stayed up late at night comparing and contrasting similarities with apartheid and American civil rights history knowing that Mandela had emerged as a great hero for both of our nations. My SA friends insisted that we visit the prison off the beautiful coast of Cape Town. Robben Island was off in the distance. The former prison for political prisoners served as “a reminder” as to why South Africa should never go back, while the wounds of apartheid were still being nurtured.

In the summer of 1999, I found myself overwhelmed with tears while touring the tiny jail cell meant to imprison Mandela. Standing in Mandela’s former cell, I retraced his footsteps and searched for clues as to how he emerged with a peaceful passion for justice and democracy. I tried to imagine the resolve it must have taken for a young and passionate Mandela to resist the weapons of anger and smuggle out political literature instead.

For anyone standing in Cell No. 5 (a facility once used as an insane asylum before becoming a maximum security prison for political enemies), it’s hard not to imagine how Mandela did not lose his resolve especially when communication, books, newspapers and letters were forbidden.

But his story reminded me that forgiveness and peaceful protest should not be mistaken for silence. It was there Mandela quietly began writing his story, “A Long Walk to Freedom,” almost as if he knew how it would end. He explained, “I was the symbol of justice in the court of the oppressor, the representative of the great ideals of freedom, fairness and democracy in a society that dishonoured those virtues. I realized then and there that I could carry on the fight even in the fortress of the enemy.” — Mandela, 1994

I never had the privilege to meet Mandela. Yet like many, I witnessed him shoulder the burden of healing a nation that was almost devastated by racial inequality. So when Mandela was unanimously elected president by the National Assembly in 1994, in Cape Town with representatives of 140 countries present, it taught me a history lesson about the real difference between retaliation and revolution.

The road to justice is worth the commitment, even if it’s a long walk. I’m eager for leadership that unites.

Rest in peace, Madiba.

There are no comments

Add yours